Open is not the Opposite of Closed

Open education. Open society in general. What does 'open' mean?

In education, openness is currently a bit of a cause celebre. Rapid recent developments in 'online' education have led many to question whether standard institutions in education are under threat, to be replaced by a variety of new models of teaching and even research that take place online.

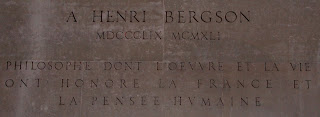

Henri Bergson was a brilliant thinker on openness. And on many other things (his Matter and Memory must still rank as one of the most extraordinary books of the last 2000 years, his Nobel Prize surely had a lot to do with that book alone). What Bergson realised was that we make the mistake of trying to define open as the opposite of closed. Just as we tend to make all sorts of similar mistakes in opposing night and day, love and hate etc. To Bergson, defining openness by making it the opposite of closed is like calling somebody a boofhead, and when they object saying, "ok ok, you're a not-boofhead then."

You can see this pattern in a lot of the discussion around new education 'open' initiatives. Open education or openness in education is described as variously:

1) free

2) available to vast numbers of people who would traditionally not enrol with a given institution

3) acting outside the normal methods of instruction and assessment, for example by removing the need for regular interaction with a teacher or tutor,

etc.

1) - 3) are all open as the opposite of closed. Traditionally education, especially at universities, costs something for the student, so free would be the opposite. And traditionally an individual university would have a limited number of enrolments, so 'massive' open enrolments would represent the opposite practice. And stripping away the traditional teaching and tutoring role in favourite of online self-assessment and other methods would, again, be the opposite of what a traditional university does.

In each case you'll notice that the educational institution is still centre stage. All that's changed is that previously 'closed' or proprietary practices are now replaced with their opposites. But opposites that still revolve around the institution, that make it the centre of that educational solar system. It still calls the shots, albeit by possibly sacrificing in some ways its previous privileges.

What else could 'open' mean?

Bergson realised that true openness is when you shift from a focus on some existing state of affairs to the relationships that create and sustain them. The outside of any organisation, object, or whatever, what you open onto, is the set of relationships that bring it into being and sustain it in existence. What Bergson did better than anybody in the history of Western thought was tackle head-on what open/closed means. He showed that there is a relative openness and relative closedness - relative to each other. So for example if I build a house, relatively my living room is inside, and my garden is outside.

But on top of that there's an absolute outside or openness, to which both my living room and the garden owe their existence. An openness that isn't about space or territory or boundaries at all. That openness isn't into a space or place, because all space is open, it's impossible to ever close anything off without it retaining some connection to 'outside' (just as biologists have shown that every point inside our bodies is actually continuous with what's outside our bodies, we're like giant Mobius strips). There is no real outside and inside, all you can ever do is mark off a bit of space (which takes ongoing work) and make a relative distinction between what's inside your mark and what's outside, even though the whole time that inside and outside remain connected. Leave your house abandoned for a few years and see how much of the distinction between inside and outside remains.

If we stick with organisations for now (although the same principles apply to a rock, a human body, a language etc.), one of the reasons that openness has come to feel like 'giving stuff away', whether that be tuition for nothing or time-honoured work practices, is that people have forgotten that every organisation is already fundamentally open to the outside. It came from that outside, and its continued existence depends on its relationships with it.

Take universities. Set up in the Australian context normally by the State, and still owned by the State. And teaching and researching with students that come from - you guessed it - outside the organisation. Without that ongoing 'open' connection, the institution ceases to exist. If you zoom out to a planetary scale, every human institution began in the mass of relations between the peoples of the world, who at various points decided to establish this or that organisation to fulfil certain functions. That seething mass of relations is always there, even after the institutions are set up, continuously injecting new meaning and resources into them, or not, as the case may be. The various interests and resources that sustain the existence of the university.

What is Openness in Education?

It's therefore possible to have a different way of understanding what open education really might be. It isn't offering courses for free, or even for money but to thousands or even millions of people. It isn't being online or using one of the many evolving mobile, online or other supposedly 'open' technologies. It's shifting the focus to the relationships behind traditional learning, and foregrounding them. Both within and outside an educational institution. Within, it's about taking traditional pedagogy, management, and anything else that goes on, and 'opening' them out to the practices, resources and ideas/research that sustain them. Moving towards opening up those practices to a continuous process of reinvention, based around ongoing practice, feedback and research (everything that brings those practices into existence and keeps them there).

Outside the institution it's not about massive online courseware or mobile technology or any other 'technology', although those may be useful in various ways. It's about focusing on the many relationships between the university as a whole and its external links - students, corporations, government, TAFEs etc. - and weaving them into the internal work of the institution in ever-more detailed and visible ways, so that relationships can be continuously created and reinvigorated.

Scaling & Continuous Reinvention

Two other characteristics of true openness are important. One is that opennness is independent of scale. When you strip things back to the relationships that sustain them, at the same time you make visible and tangible the full links between 'macro' and 'micro' things. So that, for example, everyday teaching practice and external government standards requirements coexist in that everyday work, as those standards are linked back to individual courses, subjects, assessment items etc.

Secondly a defining characteristic of true openness is that it has no 'end', both in the directional and chronological sense. Unlike traditional planning, which sets up desired end-points to reach some time in the future and then tries to work towards them, because openness means having tangible access to all of the relations underlying what's going on, and these relationships are always changing, the actual work you do and what direction you and others will head with it will be continuously changing as well.

Traditional planning makes a distinction between being proactive and reactive, and assumes that if you don't set targets and work towards them you're stuck with simply reacting to everything that happens. But that's the same false dichotomy as the open/closed one described above. If you replace more static planning with opennness, you become poised as an organisation, endlessly responsive to even small changes in all of the various relations, within and without.

What about the Technologies?

The long list of potentially 'disruptive' technologies that occupy much of the debate around open/online education are what I sometimes call "pedagogical porn." By missing what they're the surface movement of - that increasing direct linking of relationships between knowledge, education institutions and society as a whole - the technologies become fetishes. Objects of fascination. But they're disruptive only to the extent that they join the dots for people and groups (such as business) which the existing institutional arrangements in education don't. That satisfy more of the granular needs of an increasing variety and quantity of interests. Hardly ever (yet) in any really comprehensive way, which connects everything from jobs outside the university right down to individual assessment and teaching practices, but better than what may be offered to them at present. A 'technology' will only succeed in this space to the extent it allows all of those collective needs, inside and outside educational institutions, to be met, at the same time and at scale.

Within a university it will mean technologies that make visible and tangible all of the connections or relations between the everyday work of staff and the interests of those being educated and wanting educated people. In a way that makes the everyday work people do automatically connected to all of those wider interests and concerns, without it ever being about doing something extra. Once you open up to the relations underlying things, everyone is immediately 'on the same page', without needing to do extra work.

Comments

Post a Comment